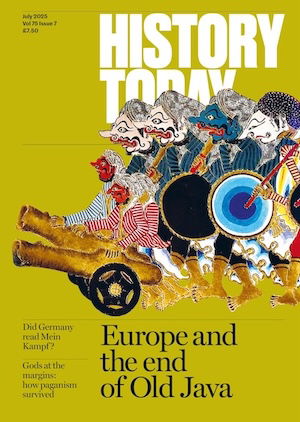

Europe and the End of Old Java

In 1825 Java’s old order rose up against encroaching European colonialism. What – and who – were the Javanese rebels fighting for?

In the late 18th century the island of Java was rocked by the waves of a political tsunami emanating from Europe. As the French Revolutionary Wars and the Napoleonic Wars – together constituting the modern era’s first global conflict – changed the continent, so did they change Europe’s possessions. The seemingly ageless Java of custom and tradition was among the casualties.

The Dutch had opened trading links with the Indonesian archipelago in the late 16th century using maps secretly obtained from the Portuguese. Drawn to the fine spices – cloves, nutmeg, and mace – of the Moluccas, and West Java’s booming pepper trade, they moved with astonishing speed to found the world’s first successful multinational, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in 1602. In 1619 the VOC base was moved from Ambon to Batavia, the former principal port of the erstwhile Hindu Sunda kingdom. Batavia would evolve into the ‘Manhattan’ of Southeast Asia, coordinating trade from Nagasaki to the Persian Gulf. As Dutch trading power grew, their political and military influence spread along Java’s north coast and began to fill the power vacuum created by the internal implosion of the sultanate of Mataram, Java’s sole remaining independent kingdom, following the death of Sultan Agung (‘the great’) in 1646.

But if the rise of the VOC was the story of the 17th century, the following hundred years – culminating in its dissolution in 1799 – was a very different tale. By February 1793, following the execution of Louis XVI, Britain and Republican France were at war. Less than two years later, French forces crossed the frozen Maas and Waal rivers and conquered the Netherlands. In Java the bankrupt VOC had to appeal to its local Javanese and Madurese allies to protect Batavia from French attack. For the Javanese, it seemed as though European power was on its last legs, but in reality the combination of industrial and political revolutions in Britain and France had unleashed the European Prometheus. These developments, in an age when the fastest journey to Europe took just under three months, were completely disguised from the inhabitants of the archipelago.

In January 1795 the Dutch stadtholder Willem V fled to London. From his temporary base at Kew Palace he issued the ‘Kew letters’, entrusting all Dutch colonies to Britain for ‘safe keeping’. This triggered a large-scale deployment of the Royal Navy in the archipelago and the British conquest of all Dutch bases outside Java between 1796 and 1810. Java itself would be controlled, in quick succession, by a Franco-Dutch regime under Herman Willem Daendels, one of Napoleon’s two non-French marshals, from 1808 to 1811, and then by a British occupation under Thomas Stamford Raffles, from 1811 to 1816.

When Daendels arrived in Java in January 1808 he found the island under siege. So rigorous was the Royal Navy’s blockade that nothing could move along the north coast without attracting the guns of its Indian Ocean squadron. But Daendels was not deterred. If a coastal highway was strategically impossible, he would use gunpowder to blast a mountain road (the ‘grote postweg’) through the Priangan Highlands. ‘No governor had thought of it before him, and I believe none will dare to contemplate it afterwards’, was one Belgian officer’s summation. Daendels’ governorship was not just about roads. It also laid the foundation for the centralisation of the Dutch East Indies, changing forever the relationship between the colonial government in Batavia and the Javanese. Tasked by King Louis of Holland (Napoleon’s younger brother) with reforming the corrupt administration of the former VOC and defending Java against the British (with sweeping powers to do so), Daendels’ 41-month tenure as viceroy transformed Java politically and socially. Among these changes was the introduction of a new way of acquiring status, importing what the British historian Norman Hampson has called ‘the nationalisation of honour’ from Europe. This mirrored the French Revolutionary dictum that ‘it is no longer one’s birth which gives honour but one’s service to the state’. In Java, a society with deep and immutable social codes, this would prove transformative.

In 1811 the British launched a successful invasion of Java, capturing Batavia on 8 August. By the time they handed it over to the Dutch on 19 August 1816 to make the United Kingdom of the Netherlands – an amalgamation of the former Austrian Netherlands and the Dutch Republic, created by the major European powers in 1815 – strong against a resurgent France, the commercial dealings of the VOC had been replaced by the beginnings of a modern colonial state. Over the following century, the reach of that state would spread across the archipelago, establishing Dutch authority in nearly every corner of what is now Indonesia until it was challenged by the nationalist movement in the early 20th century and buried by the Japanese with their victory over the Allies at the Battle of the Java Sea on 27 February 1942.

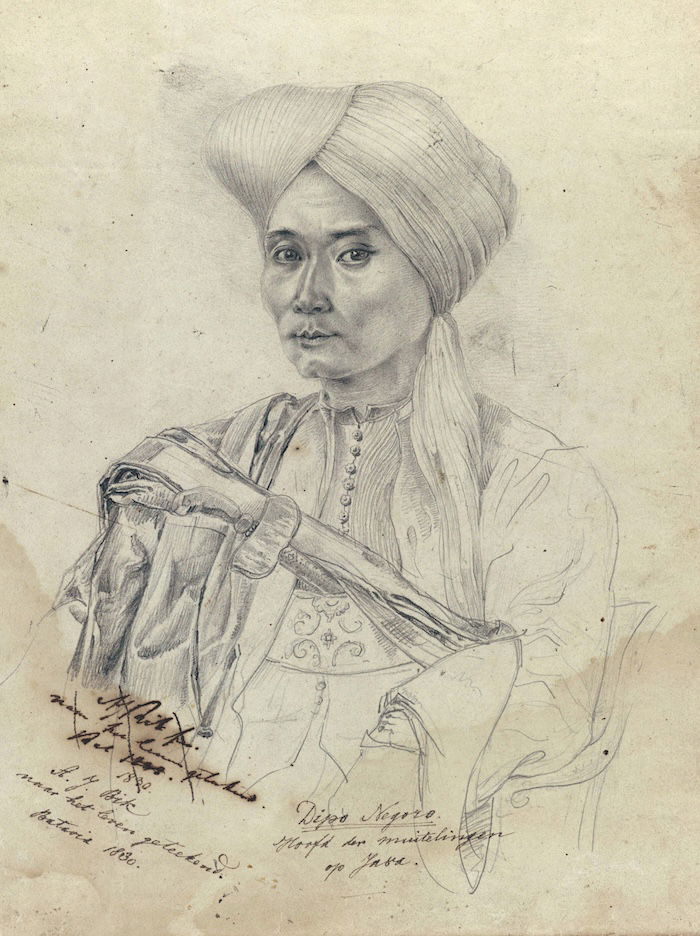

Prince Diponegoro

Java was not only changed by European affairs. Islam reached the archipelago through Muslim traders from western India in the late 12th or early 13th century, and the quickening tempo of pilgrim traffic across the Indian Ocean exposed its inhabitants to the turbulent events in the Middle East, where a French army briefly occupied Egypt and Syria from 1798 to 1801 before the puritan Wahhabis overran the holy cities of Islam from 1803 to 1812. The Ottoman Empire – despite its fading glory – inspired admiration as the one Islamic state which had seemingly withstood the might of Christian Europe, stiffening the resolve of Muslim rulers in the face of Western imperial expansion. This was especially true in Java, where the nascent power of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands came closest to defeat during a five-year struggle known as the Java War. From its outbreak in July 1825 until their final defeat in March 1830, the Javanese rebels waged a guerrilla campaign across large swathes of east and central Java. The main protagonist in this conflict was a Javanese prince from the sultanate of Yogyakarta: Prince Diponegoro.

The sultanate of Yogyakarta was also a legacy of Mataram’s decline. In 1755 the Treaty of Giyanti, brokered by the Dutch, divided Mataram’s erstwhile territory between the central Javanese courts of Surakarta and Yogyakarta. Oral tradition has it that Hamengkubuwono I, the first sultan of Yogyakarta, asked his Surakarta counterpart to choose between ‘tradition’ and ‘modernity’ – ‘wadhah’ (‘container’) and ‘wiji’ (‘essence’) – with regard to the style of his new court, to ensure that the two halves would evolve with distinct cultural patterns. Hamengkubuwono himself opted for ‘wadhah’, the Yogyanese attachment to Javanese tradition later summarised in three epithets: an ability to keep secrets, unstinting generosity, and strong religious faith.

Prince Diponegoro – ‘Dipo’ from the Sanskrit ‘dwipa’ (‘lamp’) and ‘negara’ (‘country’), ‘light of the country’ – was born in 1785, the eldest son of the third Yogyakarta sultan, Hamengkubuwono III, and a secondary wife. As a young man Diponegoro witnessed the humiliation of his father’s realm at the hands of both Daendels and Raffles. The British occupation was especially devastating, with no fewer than four courts across the archipelago – Palembang, Yogyakarta, Bali-Buleleng, and Bone – pillaged. The assault on Yogyakarta on 20 June 1812 was particularly savage. Diponegoro’s great-uncle, Prince Panular, described how the Shetland-born residency secretary John Deans posed while mutilating the body of the slain Yogyakarta army commander, Raden Tumenggung Sumodiningrat, in his private mosque. Javanese chronicles, usually sung in public gatherings, record Sumodiningrat’s ‘heart-wrenching death’ – and how Deans ‘pretended that he was the one who had killed him’. Such savagery provided the context for Diponegoro’s holy war against the Dutch in 1825.

But how ‘holy’ was the war? Rather than fighting for the caliphate, Diponegoro’s religious aims were deeply anchored in Javanese Sufism, a form of Islam that easily co-existed with the Buddhism and Hinduism inherited from the archipelago’s great pre-Muslim empires Srivijaya and Majapahit, as well as with Javanese animism. Unusually for a member of the Javanese aristocracy, Diponegoro spent his childhood in a village environment having been ‘adopted’ at birth by his great-grandmother, Ratu Ageng, the widow of Hamengkubuwono I. A lady of great piety, she took the seven-year-old prince to her country estate at Tegalrejo, three miles northwest of Yogyakarta, and taught him to mix with Javanese of all classes, in particular farmers and santri, wandering students of Islam. In his autobiographical chronicle, the prince evoked his great-grandmother’s simple life: ‘She delighted in farming / and in her religious duties. / She made herself anonymous / in her profession of her love of God.’

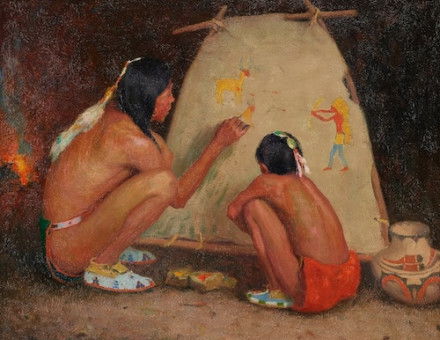

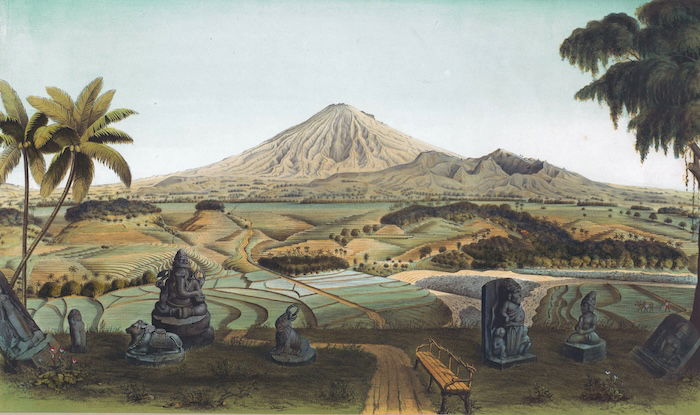

Diponegoro’s upbringing taught him to withstand physical hardships, embarking in his teens on long journeys on foot to religious schools and places associated with Java’s spirit guardians. An autodidact and keen chess player, the prince rolled his cigarettes using maize corn bracts, had a weakness for South African wine (Constantia), and loved songbirds. He sought secluded areas for meditation. Following his great-grandmother’s death in October 1803 Diponegoro built a personal retreat – Selorejo (‘stone of prosperity’) – where he could meditate on a seat made of four upturned Dhyani Buddhas on an artificial island shaded by a banyan tree surrounded by a pond filled with turtles and fish and overlooked by the great volcano, Merapi. This mix of religions was common for early 19th-century Javanese noblemen; the prince found no problem following the practices of his Sufi Islamic mystical order at a retreat filled with Buddhist and Hindu statuary from nearby temples.

In 1805, aged 20, Diponegoro made a pilgrimage to Java’s south coast. There, near the thunderous surf of the Indian Ocean, he received the visions which foretold his future role as a Javanese ‘Just King’ (‘Ratu Adil’), a ruler who would restore the moral balance of the Javanese world. We know of these visions from the prince’s chronicle. Convinced of his destiny to ‘raise up the high state of the Islamic religion in Java’, Diponegoro saw himself as an agent of purification, but he was no Islamic reformer. Instead, he would be a defender of an old order in which Javanese belief systems associated with the goddess of the Southern Ocean, Ratu Kidul, could coexist alongside the teachings of Islam.

The Java War

The world of Diponegoro’s youth had been destroyed in the aftermath of the events in post-Revolutionary Europe. The years between 1816 and 1825 were particularly dire for the Javanese peasantry. The Dutch government, bankrupted by the French occupation, sought to restore their threadbare finances by extending the system of tollgates in the Javanese countryside. That these were run by Chinese immigrants with no fluency in Javanese or Malay lit the powder keg of an anti-Chinese pogrom targeting central Java’s 25,000-strong Chinese community. Java had suffered from drought, famine, and, in 1821, an outbreak of cholera. The massive eruption of Merapi in December 1822, and the appearance of the great comet of 1825 on 15 July, five days before the outbreak of the war, quickened expectations of a coming Ratu Adil. To those who knew him from his journeys across the countryside, Diponegoro embodied this figure.

The casus belli when it came was minor: a highway project demarcated with studied insolence across the prince’s Tegalrejo estate. An armed stand-off precipitated a Dutch military expedition which torched his residence, forcing Diponegoro and 300 followers to flee to his meditation cave south of Yogyakarta. There the prince set up the standard of revolt. It was 21 July 1825: the Java War had begun.

As Diponegoro’s emissaries carried news of his rebellion, the war spread across central and east Java. In quick succession, the prince received local allies at his cave headquarters, each of whom received new Arabic names and titles as commanders in the holy war. Diponegoro’s adviser, Haji Badaruddin, had twice led official Yogya court pilgrimages to Mecca and had spent time in the holy cities, where he had observed the structure of the local Ottoman government. This exposure to Ottoman military institutions explains Diponegoro’s emulation of the ranks and regimental names used in the Ottoman army. His elite bodyguards, who wore turbans of different colours and had regimental banners with serpents, half-moons, and inscriptions from the Quran, were arranged in companies with names such as ‘Bulkio’, ‘Turkio’, and ‘Arkio’, directly modelled on the Bölüki, Oturaki, and Ardia janissary corps of the Ottoman sultans.

The Java War was a guerrilla conflict marked by ambushes, rapid movement, and unconventional attacks designed to surprise. It was also a delegated affair loosely coordinated by Diponegoro at the centre. Regional leaders took the initiative in their localities. Among these were the family of the respected apostle of Islam, Sunan Kalijaga. Hailing from Java’s north coast near the ancient mosque city of Demak, this family included Diponegoro’s most feared female commander, Nyai Ageng Serang, who, on the night of 2 September cut a 300-strong Dutch column to pieces. Only 50 cavalry escaped with their Dutch captain. The captured Madurese pikemen were spared as fellow Muslims, but the rest, mainly sailors from the Dutch frigate De Javaan, were flayed alive. Such scenes were repeated throughout the main theatres of war, which stretched from Banyumas in the west to Ponorogo in the east. Dutch-held Yogyakarta – then nominally ruled by the infant sultan Hamengkubuwono V – was closely invested by the prince’s army. As its inhabitants starved, many slipped out at night to join the rebels.

The tide turns

The Dutch, led from 1825 by Hendrik Merkus de Kock, scrambled to regain the initiative. Unexpected reinforcements came with the return of an expeditionary force under de Kock’s deputy, J.J. van Geen, which had just completed a campaign against the sultanate of Bone in South Celebes. This saved the colony’s third city, Semarang, following Nyai Ageng Serang’s September victory. But it was not enough to turn the tide. The first year of fighting witnessed a see-saw between almost equally matched Dutch and Javanese forces. Nearly two years were lost before de Kock and his advisers devised a winning strategy: the combined use of temporary fortifications (‘benteng’) with an increased number of flying columns.

Why did it take the Dutch so long? The answer must be sought in the glaring inadequacies of the colonial army. Deficient in resources, its officers took time to understand the nature of the war. During the first two years, 6,000 infantry were deployed with a further 1,200 artillery and cavalry against Diponegoro’s estimated 20,000 troops. Although close to 2,400 men were sent from the Netherlands during the course of 1826 to replace those killed and wounded, they could not be immediately deployed because of the challenges of the terrain and climate. Their classic European military training was found to be a poor preparation for the counter-insurgency warfare they were called upon to fight in Java. Many succumbed to disease soon after arriving. Of the 6,000 European infantry on active service between July 1825 and April 1827, 1,603 perished. Nor was the presence of large numbers of native auxiliaries much help. With the exception of the Madurese, many were of doubtful military value. Opium addiction and an insistence on bringing their families on campaign complicated the logistics of moving through enemy-held territory, turning what should have been a tight 500-strong flying column into a lumbering juggernaut which looked more like a baggage train than a military formation.

The Javanese, in contrast, proved excellent guerrilla fighters, able to subsist on dried rice and edible roots. They learnt how to wear down the enemy without allowing them pitched battles. In 1826 Diponegoro’s forces, commanded by the prince’s 17-year-old adopted son Sentot, won a series of victories in quick succession, bringing a large proportion of the central Javanese heartland under Diponegoro’s control. Van Geen described how Diponegoro’s forces would storm the Dutch lines in a frenzy with blood-curdling shrieks and lowered heads. (Van Geen, for his part, was especially hated for his scorched earth tactics, summary executions, and habit of burying his enemies up to their necks to be eaten by insects.) In desperation, the Dutch began stripping the outer islands of troops and by late 1828 the tide was starting to turn against the prince, whose remaining forces were gradually hemmed into an increasingly narrow strip of territory between the Progo and Bogowonto rivers. By the end of September 1829 organised resistance to the Dutch in the fertile rice plains of south-central Java was at an end. The bond between Diponegoro’s forces and the local population had been sundered by de Kock’s benteng system – without them there could be no successful guerrilla campaign. On 11 November 1829 the prince narrowly escaped capture in an ambush by leaping into a ravine. Thereafter he retreated into the jungles of Bagelen, accompanied by two intimate retainers. These wanderings continued until February 1830 when the prince’s first direct negotiations with the Dutch began. An abortive ‘peace conference’ with de Kock at Magelang in March 1830 resulted in Diponegoro’s arrest on 28 March, and exile soon thereafter.

The price of peace

The Java War can be seen as the last stand of Java’s old order, marking the final transition to the high colonial era of the Dutch East Indies state, formally established in 1818. The spirit which animated Diponegoro’s followers was characterised by one Dutch official as a ‘feeling of [Javanese] nationality’, but it was also a demand for respect for Javanese culture. We see this in Diponegoro’s treatment of Dutch prisoners, insisting they speak High Javanese to their captors rather than market Malay, the lingua franca of the colonial state, dress in Javanese style, and consider conversion to Islam. This last was something the prince also expected of the Chinese who sided with him, the process of ‘becoming Muslim’ being quite simple: cutting off their pigtails, undergoing circumcision, and uttering the shahada: ‘There is no God but God and Muhammad is His Prophet.’ Despite a number of his close friends and family being of Chinese descent, including his favourite uncle, Diponegoro embraced anti-Chinese sentiment at the start of the war, forbidding his commanders from having relations with peranakan (of mixed Chinese and Javanese descent) women and blaming his defeat at Gawok in October 1826 on his dalliance with a Chinese prisoner-of-war who had acted as his masseuse on the eve of the battle.

In his peace proposals at Magelang, Diponegoro presented the Dutch with three options: return to their country and continue to trade with Java; remain in Java as traders, but reside in three designated north coast cities (Batavia, Semarang, Surabaya); or embrace Islam and be rewarded with enhanced civilian and military rank. The first two options came with a further condition: the Dutch would be required to pay international prices for Javanese products. Diponegoro’s insistence on market prices was prescient considering what happened next. The Java War consumed the lives of 200,000 Javanese and damaged the livelihood of two million more, a third of the population. The Netherlands’ victory cost them 15,000 troops (8,000 European) and bankrupted their colonial exchequer, leaving them with a 25 million guilder debt. Due to this debt, in 1830 the Dutch instituted the ‘Cultivation System’, which required Javanese villages to set aside part of their land to produce export crops, especially coffee, sugar, and indigo, for sale at fixed prices to the colonial government. Within 40 years the Dutch had made 832 million guilders, the equivalent in purchasing power parity terms of $100 billion in today’s money. This capital eased the Netherlands’ transition to a modern industrial economy, enabled it to pay off most of its state debt, finance infrastructure (canals and railways), and fortify its southern border against French attack. This exploitative relationship inspired Eduard Douwes Dekker (‘Multatuli’) to dedicate his explosive novel Max Havelaar (1860) to the Dutch king, Willem III, that ‘thief on horseback’ and ruler of the ‘robber state on the North Sea’.

Diponegoro’s return

In the end it was the marked religious character of the war that caused the minister of the colonies, Cornelis Theodorus Elout, to reject suggestions made by some Dutch officials that hostilities should be brought to an end by recognising Diponegoro as an independent prince in the same way that his great-grandfather had been in 1755. In Elout’s view, Diponegoro’s claim to be a protector of religion, and his intimate associations with religious communities, made any such concessions impossible. The war’s religious aspect set it apart from the dynastic struggles of previous centuries.

Diponegoro would spend the final 24 years of his life in exile in Celebes – first in Manado, then in Makassar, where he died of natural causes on 8 January 1855. During that time he wrote his autobiography, the Babad Diponegoro, 1,150 folio pages recognised by UNESCO as a Memory of the World manuscript in June 2013. Recounting the ancient history of Java, he wrote the chronicle in part for the education of his seven children born in exile, whom he wished to bring up as Javanese, not Makassarese or Bugis. In 1831 a wandering Javanese man, Joyoseno, raised supporters by declaring that Diponegoro had returned to Java. His movement was dispersed when he was captured by the Dutch authorities, but later in the same year two other followers raised a significant following by proclaiming that Diponegoro was back, and was in his cave in Bagelen. As late as 1849 a plot was supposedly foiled to bring Diponegoro back from Makassar and declare him sultan.

When the Indonesian nationalist movement began to organise in the early 20th century – driven partly by a group of Indonesians living and studying in the Netherlands – Diponegoro’s name again became a unifying inspiration. He was able to unite the communists, who recognised the prince’s concern for the people, the nationalists, who championed Diponegoro’s defence of Javanese values, and the Muslims, who admired his use of Islam as a rallying point against the Dutch. Today, his frugality and hatred of corruption make him an uncomfortable presence for those Indonesian politicians who do not share these characteristics. In the palace at Yogyakarta all portraits of the prince have been removed and his name banned from the list of accepted titles for senior princes, due to his attack on the court and betrayal of his duties as royal guardian to the infant fifth sultan. But following Indonesia’s proclamation of independence on 17 August 1945, and the country’s victory in another independence war against the returning Dutch, Diponegoro was recognised as a national hero in 1973 – a hero in a country not imagined in his lifetime.

Peter Carey is Fellow Emeritus of Trinity College, Oxford.