Did Germany Read Mein Kampf?

A huge bestseller and undisputed guide to the Nazi worldview, did Germans actually read Mein Kampf?

On 11 April 1942, during one of Hitler’s habitual monologues before his inner circle at the ‘Wolf’s Lair’ headquarters in East Prussia, talk turned to Alfred Rosenberg’s book The Myth of the Twentieth Century. The Nazi theorist’s notoriously impenetrable volume, first published in 1930, had become one of the core ideological texts of the Third Reich, in which Rosenberg proffered, in almost unreadably dense prose, a racial history of the world and argued for the Aryan race’s inherent, yet embattled, superiority. Hitler had personally awarded the author the newly instituted German National Order for Art and Science in January 1938. Yet four years on, Hitler’s private comments were dismissive. The publishers, he noted, had had ‘great difficulty in disposing of the first edition’. Furthermore, the book’s core readership was to be found mostly outside the Nazi movement. Interest in the book had been largely driven by Catholic opposition to it. He added that the book ought not be regarded as representing the Nazi Party’s official ideology; as Hitler confessed, ‘like many’ he had only given it the most cursory of glances due to its ‘abstruse’ style.

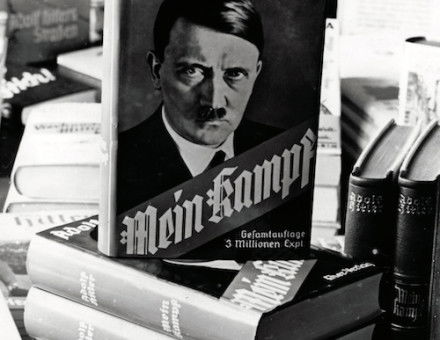

Few would have disagreed: the subtitle of Rosenberg’s tome – rendered, if anything, less unwieldy for the English translation as ‘an evaluation of the spiritual-intellectual confrontations of our age’ – was a daunting foretaste of the stylistic approach within. Yet there was an unknowing irony here: Mein Kampf, Hitler’s own book, was also famously difficult to read. Historians have long assumed that no one did so. Indeed, many of the Nazi elite admitted to having struggled, or to have read only parts of it. Julius Streicher, former regional leader in Franconia and publisher of the antisemitic newspaper Der Stürmer, assured the Nuremberg tribunal of the ignorance of the Nazi defendants with regard to Hitler’s book; as for himself, he claimed his reading had been limited to ‘only what concerns the Jewish question’. A monomaniacal antisemite even by the regime’s standards, this seems plausible in Streicher’s case. Yet others struggled too: many were the stalwart Nazis, the American journalist William Shirer claimed, who had confided in him that they had found it heavy going at best; ‘not a few’ confessed to having been defeated by it altogether.

A book conquers a people

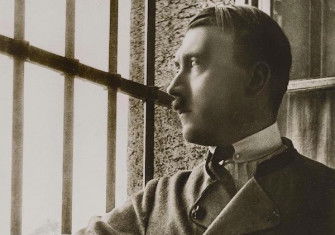

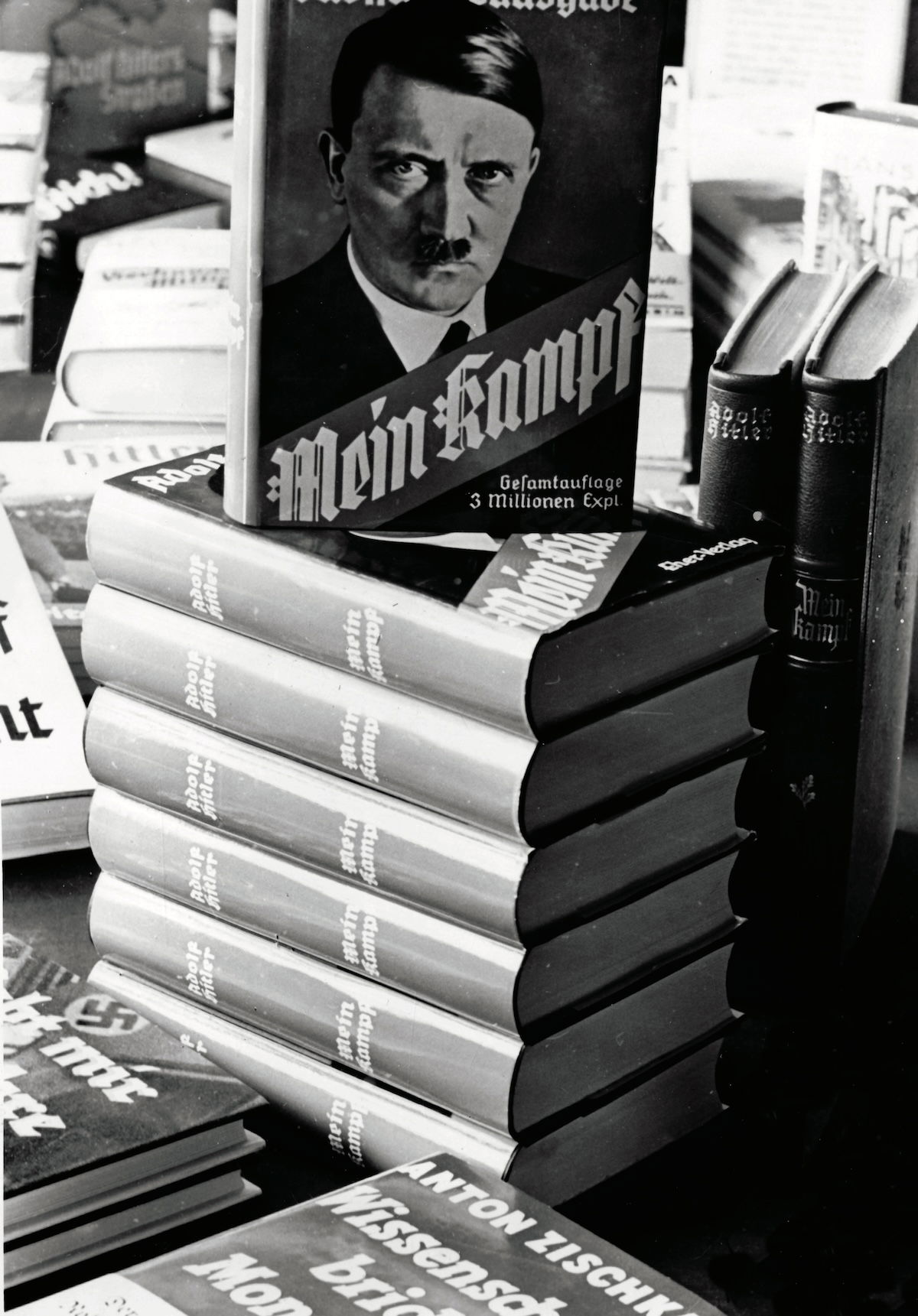

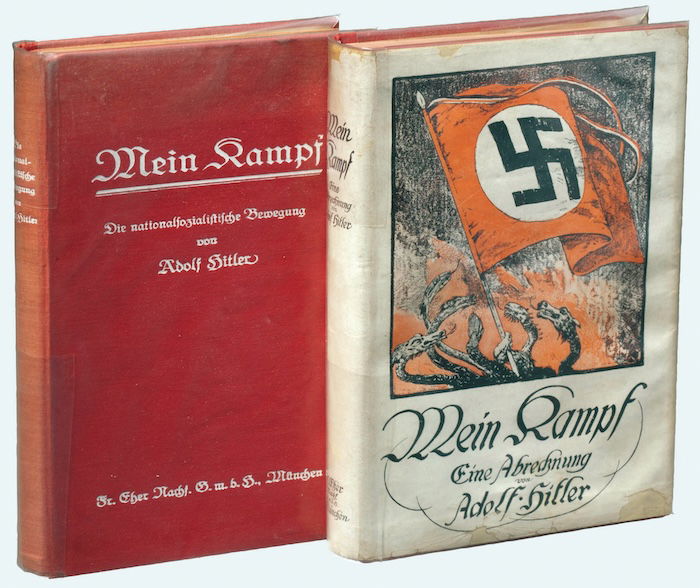

Is there more to the story? Fifteen years after the end of the war, a documentary about the Third Reich, named after Mein Kampf, prompted a joke to make the rounds in West Berlin. As two former Nazis leave the cinema together, one remarks to the other: ‘I preferred the book.’ The joke turned on the idea, attractive in the immediate postwar era, that Mein Kampf had been read by few and scorned by most. Here the figures alone might give one pause: by 1944 just under 12.5 million copies of the book had been produced. Originally published in two volumes, the first, written during Hitler’s detention in Landsberg following the ‘Beer Hall Putsch’, was published on 18 July 1925 in an initial run of 10,000 copies. The second was written over the following 15 months, completed by November 1926 and published on 11 December 1926. A later, cheaper, ‘people’s edition’, combining both parts in one volume, followed in May 1930. Marking the tenth anniversary of the first volume’s publication, an exhibition held at the 1935 Nuremberg rally admitted that the initial first edition had been relatively expensive at 12 Reichsmarks, but that this had failed to hinder sales: a further print run of 8,000 had proven necessary in the first six months. The not-so-subtle point was that even at this early stage Germans were being drawn irresistibly to Hitler’s book – and thus to the man himself.

Yet the first volume had also proven more popular than the second: as of the end of 1929 the print run of the first totalled 23,000 copies, that of the second 13,000. This seems telling in itself, indicating, perhaps, that the first volume was felt to be enlightenment enough for many readers. The booklet accompanying the exhibition noted that the ‘people’s edition’, within the means of many more people at a price of eight Reichsmarks, sold more rapidly. Some 52,000 copies had been produced by the end of 1930, and a further 142,000 copies had apparently been sold in 1931 and 1932 combined, the exhibition explained, an average of just under 6,000 per month or slightly less than 200 daily.

Despite coinciding with the Nazi movement’s electoral breakthrough – the NSDAP became the largest party in the Reichstag at the July 1932 elections – the slower pace of sales in the last two years of the Weimar Republic was perhaps attributable to the economic crisis, with unemployment hitting six million in Germany in 1932. Yet it also reflects the impression that the book seems to have been the ideological route into the Nazi movement for only a few. Typically, Nazi footsoldiers recalled reading the book, if at all, only after first becoming acquainted with Nazism elsewhere. Karl Friedrich Nau, from Hesse, recalled first attending Nazi assemblies aged 17 in the spa town of Bad Nauheim. It was these meetings that fired his enthusiasm: only then, already ‘for Hitler’, did he buy a copy of Mein Kampf during a period of sick leave after a minor workplace injury. ‘I read it through thoroughly’, he recalled, ‘as far as my young brain could comprehend it.’ Engagement with the book reflected burgeoning convictions, cementing rather than creating them: Nau joined the Nazi party days later.

Others formed discussion groups, reading and sharing ideas about the book in detail, as former stormtrooper and journalist Willi Habsheim recalled doing as an 18-year-old student in Mannheim. But this level of detailed engagement seems to have been rare. A survey of 120 respondents conducted in 1968 by Karl Lange, a German historian at the Technical University in Braunschweig, found 27 Germans admitting to having read the book prior to Hitler becoming chancellor in 1933. Of these, 11 claimed to have read it in full, while 16 said they had only read parts. Cartoons in the Weimar press showing Hitler desperately hawking copies around a beer hall reflected a reluctance to take the book seriously, as did a 1932 incident recalled by a participant in the survey. As they told it, a bookshop owner had been asked by a Jewish customer to take a copy of the ‘dangerous’ book out of the display window. His insistence that war would ensue if Hitler came to power was dismissed, the proprietor countering by asking whether the book really ought to be taken so seriously. Keenly aware of such attitudes, Nazi propagandists poured scorn on those who, having belittled the book previously, rushed to add it to their shelves after Hitler became chancellor. True National Socialists, threatened an article marking the book’s tenth anniversary in the Party’s national daily Völkischer Beobachter, would ‘closely watch’ those now hypocritically claiming to always have sensed the book’s greatness. The celebratory piece was published under the headline: ‘A Book Conquers a People.’

‘What will Hitler do?’

The surge in interest in the book following Hitler’s January 1933 appointment was genuine; the landmark figure of a million copies in circulation was reached that September. Yet this was only partly attributable to a ‘general enthusiasm for the New Germany’, as the same article conceded. It was also due to general curiosity, as well as a sense of self-preservation. The regime’s own figures show interest slowing, albeit remaining significant, in the second and third years of Nazi rule: from 1,215,000 copies sold in 1933 alone, to 568,000 in the 20 months between the beginning of 1934 and the Nuremberg rally in September 1935. In other words, 100,000 per month on average in the regime’s first year, but fewer than 30,000 monthly in the latter period. Nevertheless, this allowed the regime to claim that the milestone of two million copies had been reached by the time of the rally.

Copies in German homes were one thing, reading the book quite another. A sense of obligation led members of Nazi organisations to purchase the book for appearance’s sake: 30 years on, a respondent to the postwar survey admitted having bought the book in 1939 as an ‘enthusiastic’ Hitler Youth member solely because he had felt he ought to have a copy on his bookshelf, but had barely touched it thereafter. In Munich, a man planning to join the Reich Labour Front’s ‘industrial brigade’ (Werkschar) – an organisation proselytising for the Nazi cause in the factories – recalled needing ‘to learn about National Socialism’. ‘Therefore’, he added, ‘I read from Mein Kampf as often as I could.’

Many now availed themselves of the book to make sense of where Germany might be heading under its new chancellor. This impulse, too, was acknowledged, indeed encouraged, in Nazi Party messaging: the day after Hitler’s appointment as chancellor, an advertisement in the Völkischer Beobachter observed that ‘millions of hopeful Germans’ were now wondering ‘what will Hitler do?’ The answer, it suggested, lay in the ‘Book of the Day’: neither ‘friend nor foe’ could afford to ignore Mein Kampf any longer, as Hitler’s ‘wishes and goals’ were set out therein. Another threat was voiced in the concluding promise that the book was now available ‘from all German bookshops’, an implicit warning to booksellers not to place themselves outside the national community by failing to stock the Führer’s opus.

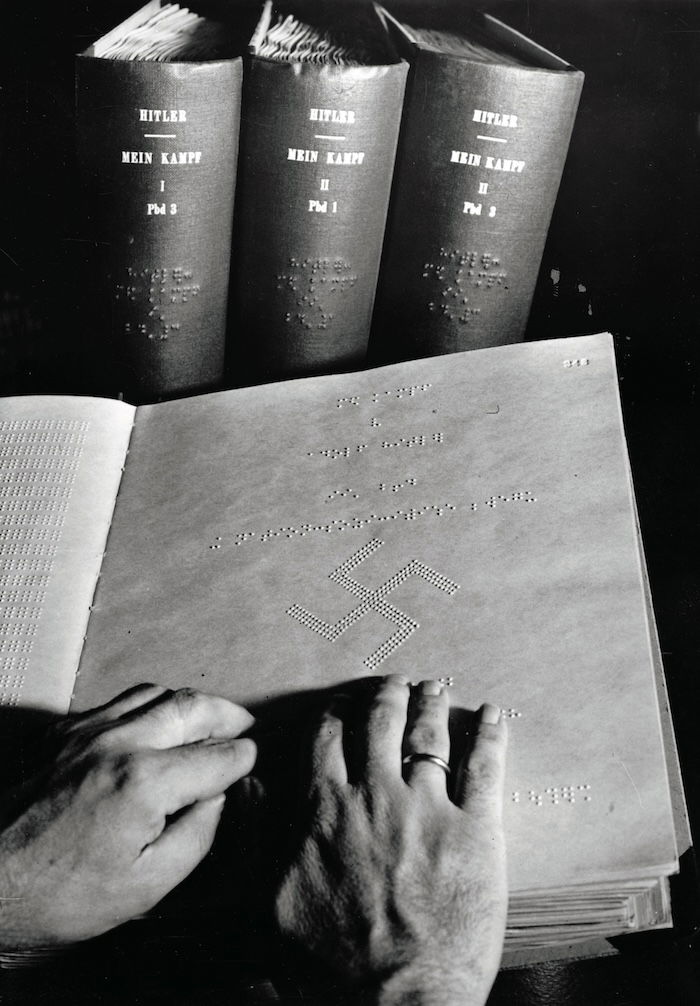

In due course the authorities would have cause to complain of the opposite problem: by the decade’s end, copies were turning up in antiquarian bookshops with alarming frequency. In October 1938 the head of the Reich Chamber of Literature felt the need to order that shops remove used copies of Mein Kampf from sale, as all true National Socialists would be pained to see ‘the work of our Führer described in our time as “second-hand”’. Clearly not all Germans were so enamoured of the book or its author as to wish to hold onto the volume permanently. But the problem was likely exacerbated by the state itself: the great efforts expended to provide its people with copies would have led to some households possessing duplicates. State registry offices were required to present newlyweds with a copy, thanks to an ordinance of the interior ministry in spring 1936; seven weeks later the policy was extended to provide for a braille edition to be presented to couples where one party was blind. Hundreds of thousands of copies of the ‘people’s edition’ were distributed thus over the next nine years.

Meanwhile, in summer 1936, the mayor of Berlin provided a list of 14 books ‘recommended’ as gifts for public sector workers when marking 25 years of service. Rosenberg’s book (‘unabridged’) was among the suggestions, likewise Joseph Goebbels’ diary account of the Nazi seizure of power, Vom Kaiserhof zur Reichskanzlei. Employees of a more intellectual bent might be rewarded with Die Juden in Deutschland, a 400-page pseudo-scholarly explication of Jewish criminality, corruption, immorality, and dominance published in 1935 by the propaganda ministry’s new ‘Institute for the Study of the Jewish Question’. A biography of Field Marshal August von Mackensen was a possibility for the military history buff. But there was no surprise which book topped the list: Mein Kampf was specified as the preferred choice, at least in such cases where the recipient was ‘not yet in possession of this book’.

Required reading

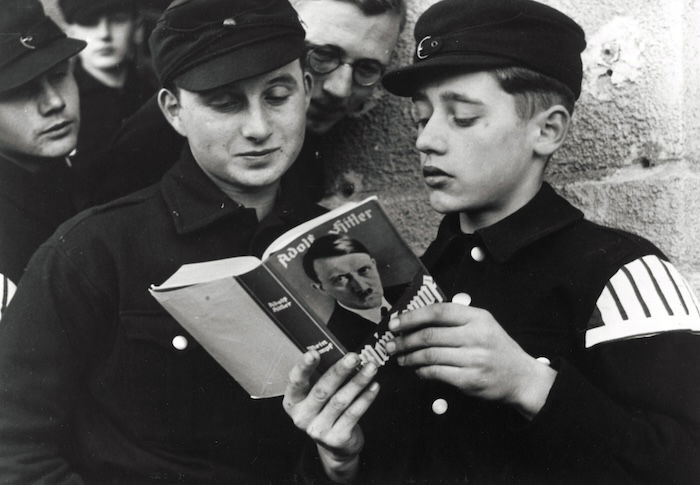

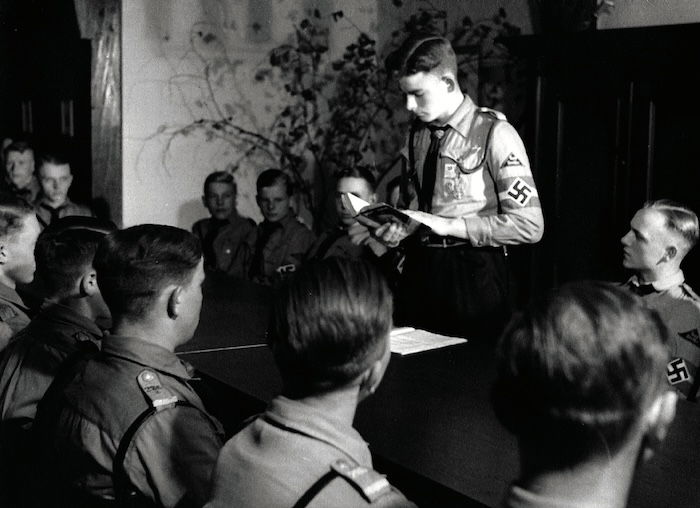

For many, engagement with the text was now compulsory. Mein Kampf became a key part of the training curriculum for the police, the stormtroopers, and for the SS Death’s Head Regiment guarding the concentration camps. In some cases the book was inflicted on the inmates: the Manchester Guardian reported in August 1933 that readings from it were forced on the 300 prisoners at Breslau-Dürrgoy concentration camp, ‘one of the most dreaded’ in the Third Reich. Stormtroopers had numerous extracts from the book set for their ‘ideological training’, its first 35 pages – offering insights on the person of the Führer – among them. After the war, many Germans recalled being ‘forced’ to read parts of the book in a professional capacity, for example on the National Socialist Teachers’ League’s training course. Journalists were quizzed on the book in examinations, and became adept at parroting quotations.

For the mass of the population, however, other methods were necessary to encourage, or ensure, exposure. Libraries were generously stocked with copies: the library in Essen, serving a population of around 650,000, held 120, a typically generous provision. Copies were borrowed, and read, but hardly in the numbers that the regime hoped. In the 1968 survey, 61 of the 120 respondents admitted to having read the book following Hitler’s appointment as chancellor. Of these, just two claimed to have read it in full, with 59 having read only parts. Yet engagement was real, and sales figures fail to capture its full extent – not all who owned the book read it, and some read the book without owning it.

Cases tried before the regime’s ‘Special Courts’ in the 1930s show that at least some Germans not only read their copies of Mein Kampf but lent them to others. Denunciations to the Gestapo followed when the borrower commented dismissively on returning the book, or discovered critical annotations – in itself evidence of close and critical engagement – in the copy they had been lent. A Munich man was hauled in for questioning after his maid spotted dozens of marginal notes in his copy; these had been reported to the secret police shortly after she had been dismissed from her job. The Gestapo searched his flat, then his book, scrupulously noting the offending annotations (‘twaddle! These last paragraphs are blasphemy! Herr Hitler’s private Teutonic God!’). Informing on fellow citizens for failing to sufficiently respect the book reflected internalisation of its totemic importance, underscored by propaganda referring to it as the ‘bible’ of the Nazi worldview. Social stigma followed remaining aloof from the book. A Hanover schoolgirl had been embarrassed when an assignment required reading a chapter from the book, owned neither by her nor by any of her friends, her father recalled after the war. Another schoolgirl in a nearby Lower Saxon town was presented with a copy upon winning a race at her school’s sports day. Her family’s Social Democrat convictions were well known in the community and she was handed the book by her teacher with the pointed advice: ‘Your father should read it, too.’

Quote of the day

Yet owning and reading Mein Kampf was far from the only context in which it was encountered in the Third Reich. Whole books were published collating quotes from, or offering a guide to, Hitler’s tome. Textbooks, from history to biology and ‘racial studies’, filleted the volume for instructive quotes, and school assemblies marking significant dates in the Nazi calendar set time aside for solemn readings from the stage.

Nor were adults spared: readings from the book were sat through at commemorative events, often sparsely attended, to the organisers’ dismay. Free admission had not ensured a full house for a Sunday morning commemoration in Ansbach of the 22nd anniversary of the founding of the Nazi Party. A report on the event in February 1942 noted that the venue had been ‘filled well, but not completely’, before reassuring, perhaps defensively, of the ‘very dignified’ effect nevertheless achieved.

The sheer scale of the book meant an appropriate quotation could be found for most occasions. The assertion by a respondent to the 1968 survey, recalling that their knowledge of the book was based solely on extracts in the newspapers, could certainly be interpreted as an apologetic, postwar distancing from Hitler’s worldview, but is plausible enough given the frequency with which words from Mein Kampf were deployed in the press. Reduced by January 1945 to a mere four pages due to paper shortages, the Völkischer Beobachter urged readers to engage in physical exercise each day with reference to Mein Kampf, wherein Hitler had himself advocated it to foster ‘flexibility, strength and agility’ and to build confidence. The latter was increasingly at a premium as the war front drew ever closer, a reality which intruded only briefly, and obliquely, in the journalist’s laconic observation that achieving this daily goal was currently challenging, but that ‘even a little is always possible, and better than nothing’.

By this juncture, Germans were pulling their copy of the book from the shelf for inopportune reasons. Turning points such as the beginning of the war with Britain and France, and the invasion of the Soviet Union two years later, had previously prompted readers to review Hitler’s remarks about those countries for a sense of his intentions. Hitler had ruminated on the ‘eternal conflict’ between France and Germany, urging that it be resolved in a ‘final active reckoning’ with the Reich’s western neighbour: ‘a last decisive struggle with the greatest ultimate aims on the German side’. The ‘destruction of France’ would enable Germany ‘finally to give our people the expansion made possible elsewhere’, he added. Four months after the Allied liberation of Paris, secret police observers across Germany noted that since the defeat at Stalingrad Germans had been discussing the book’s advocacy of expansion into Eastern Europe, sharing with each other the conclusion that ‘culpability for the war clearly lies on our side’, and that a war for territorial expansion had been Hitler’s plan from the outset. A perfunctory examination of the book would have been sufficient: a chapter devoted to ‘eastern orientation’ found Hitler demanding Germany ‘take up where we broke off six hundred years ago’ and ‘turn our gaze towards the land in the east’ – specifically, ‘Russia and her vassal border states’.

Burning bibles

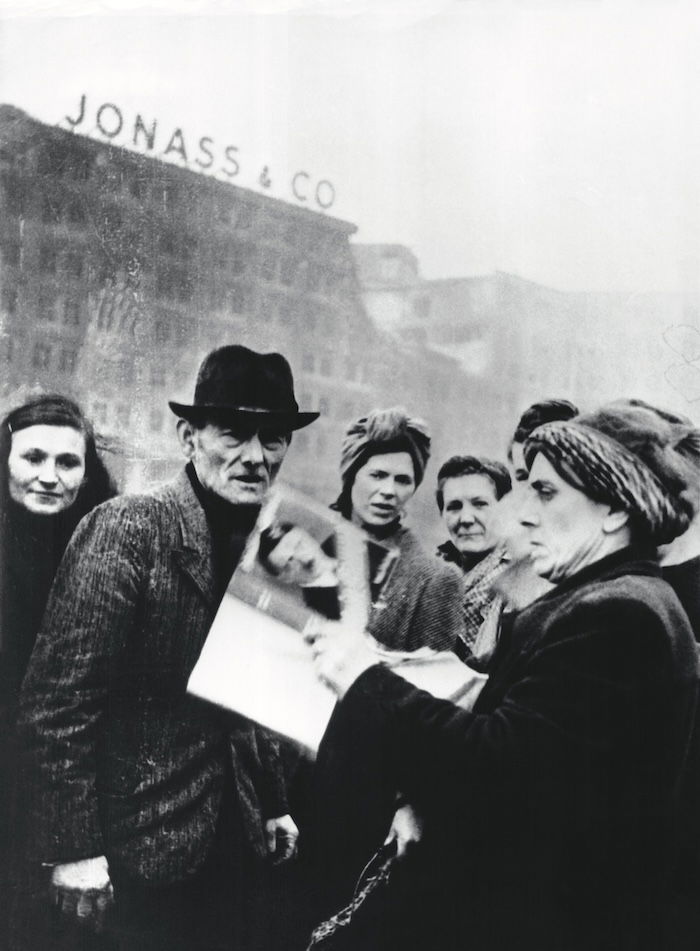

Impending defeat only increased critical, albeit belated, engagement with the book. While in Britain a mock-up of the book was burned along with a Hitler effigy at VE Day celebrations, Germans reached for their copies once more – this time to consign them to the flames. Ownership of the book was now potentially incriminating in the eyes of the Allied occupiers. So many now quietly burned, buried, or threw their copy in the nearest river, that an official of the US military government complained of struggling to find even 150 copies, out of the millions so recently in circulation, in the entire US zone.

The book had been a ‘bible’ of the Third Reich in more ways than one. It had been a definitive statement of the Nazi worldview, an endlessly quotable repository of wisdom for the true believer. Yet it had also, like the Bible, been read in full by few, in part by more, and barely or not at all by most, the copy on the shelf gesturing towards, although not conclusively demonstrating, commitment to the faith. In many households the book had sat gathering dust unread until moments of crisis prompted its owner to leaf through its pages in search of guidance and instruction.

Paul Moore is Lecturer in Modern European History at the University of Leicester.