Nasser, Suez, and the Muslim Brotherhood

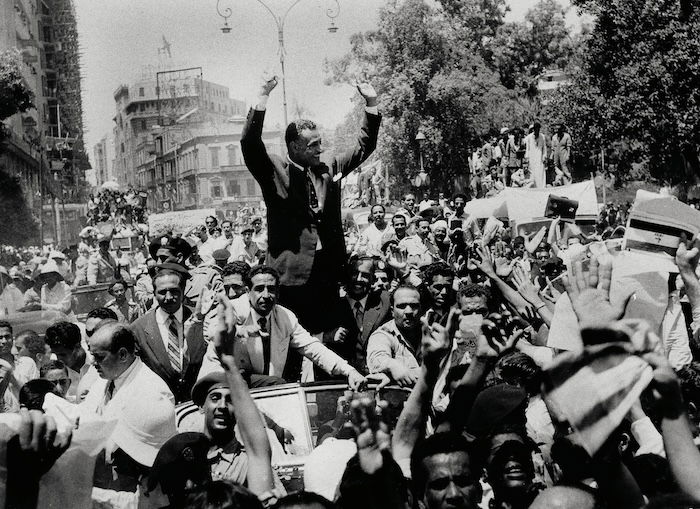

As Nasser moved to nationalise the Suez Canal in 1956, Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood was forced to choose between faith and freedom.

In the mid-1950s, as Cairo buzzed with tense negotiations over the fate of the Suez Canal, a different kind of battle smouldered beneath the scorching sun of the Western Desert. In the large prison camp known among locals as ‘Wahat’, recently imprisoned members of the Muslim Brotherhood were engaged in an internal war of belief and loyalty. As President Gamal Abdel Nasser prepared to defy the West by nationalising the Suez Canal in 1956, the Muslim Brothers faced their own reckoning: should they support a regime that had brutalised them, simply because it now claimed to defend the homeland?

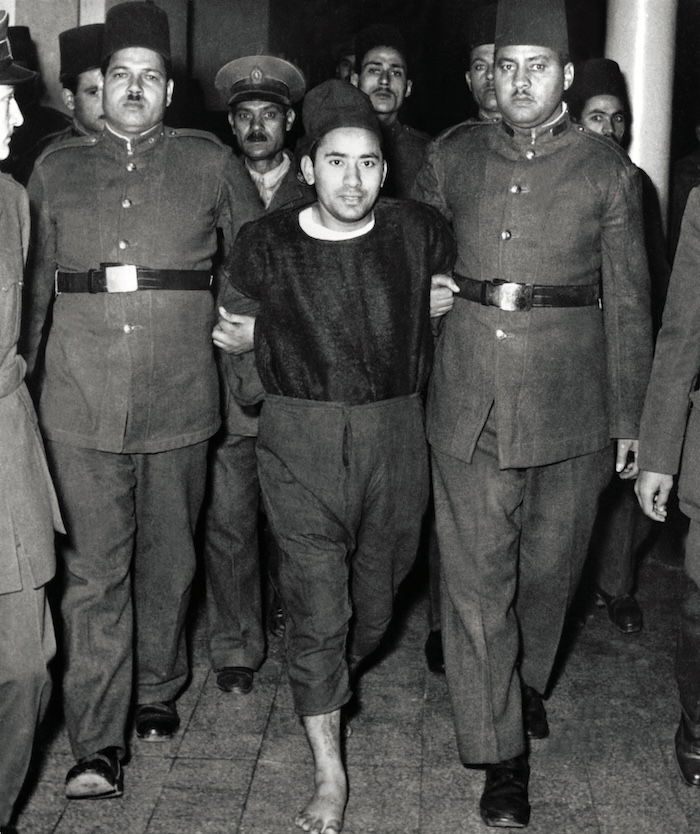

Two years earlier, in late 1954, thousands of Brotherhood members had been imprisoned following a failed assassination attempt on Nasser in Alexandria. The gunman – a young repairman from Cairo – had acted on orders from the Brotherhood’s paramilitary wing, the Secret Apparatus, unbeknown to much of the organisation, including its newly appointed leader, Hasan al-Hudaybi. The incident gave Nasser a convenient pretext: after years of watching the Brotherhood’s influence grow, he could now publicly justify dismantling a powerful political rival, the largest Islamist organisation in Egypt.

Founded in 1928 in Ismailia by street preacher and schoolteacher Hasan al-Banna, the Muslim Brotherhood was among the first and most influential Islamist movements. Opposed to Egypt’s political elite, British colonial rule, and foreign missionaries, it grew rapidly during the interwar years into a mass social movement, establishing schools, mosques, orphanages, and factories to appeal to – and compete for the support of – Egypt’s growing middle class. Aiming to halt Egypt’s westernising trajectory and establish an indigenous Islamic social and political order, the Brotherhood sought to purge the existing regime and replace it with its own more religiously oriented cadres. Critical of parliamentary politics, the Brotherhood increasingly focused on grassroots activism and, in the 1940s, with the rise of the Palestine issue, parts of the Brotherhood turned paramilitary. More than a thousand Brothers fought in the 1948 war over Palestine. By the 1950s the Brotherhood had become a major political force, often clashing with Egypt’s new rulers, the Free Officers led by Nasser after the revolution of 1952 which had toppled King Farouk and made Egypt a republic. A wave of violent attacks that struck Cairo and Alexandria in the late 1940s and early 1950s – some correctly and others incorrectly attributed to paramilitary elements within the Brotherhood – prompted successive governments to dissolve the movement on multiple occasions. Although there was a brief rapprochement between leading Brothers and the Free Officers following the revolution, the relationship had soured by 1954.

The Suez crisis of 1956 did not just shake international politics but also tore apart one of Egypt’s most influential politico-religious movements. As news of the mounting international crisis reached Camp Wahat, the Brothers were presented with a choice: support Nasser, or oppose him.

Seeds of division

During their pre-trial detention in Cairo’s notorious military prison, the Brothers had been subjected to horrific abuse, including whippings, beatings, electrocution, disfigurement, and sexual assault. Their testimonies are preserved in hundreds of prison memoirs written by members of the Brotherhood, either while incarcerated or after their release. But their accounts do not stand alone. Since the death of Nasser in 1970 a wealth of material has come to light, mostly in Arabic. It includes prison memoirs by other political detainees – communists, politicians, and Zionists – alongside novels, poetry, and plays written and performed behind bars, as well as state propaganda, intelligence cables, and the official records of the Egyptian prison service.

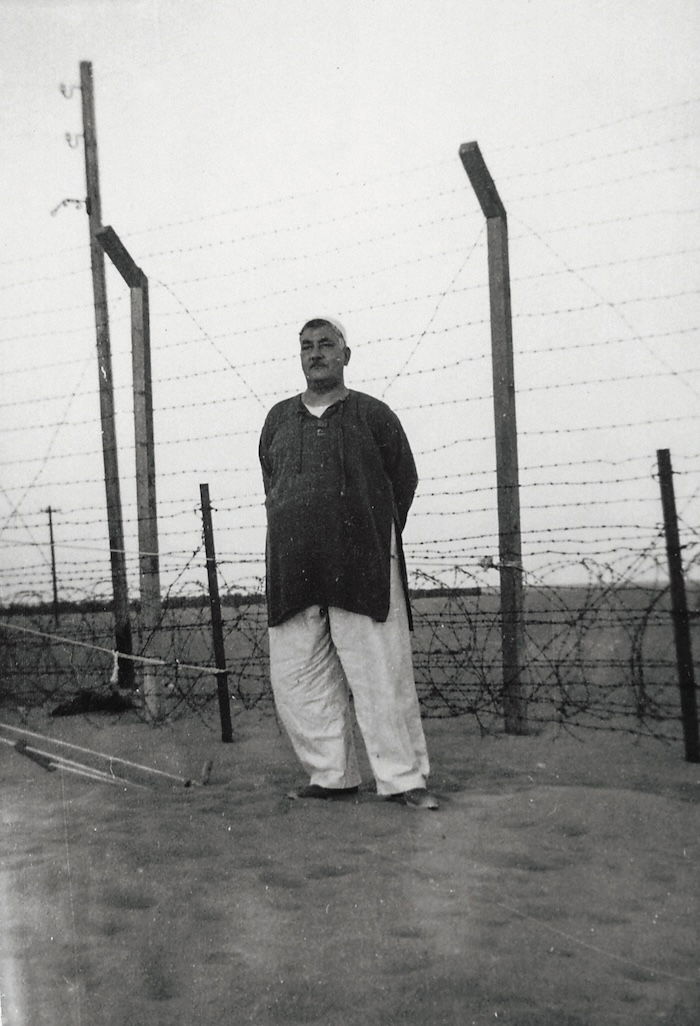

Following their show trials in 1955, the Brothers were sent to prisons all over Egypt. While most ended up in standard brick-and-mortar facilities, around 500 of the group’s most prominent members were loaded onto trains and taken south into the Western Desert. A few miles from the Kharga Oasis, they were held behind coils of barbed wire in the newly built Camp Wahat. The camp was utterly desolate – nothing but sand in every direction, with only a minimal guard presence. As some of the Brothers later recorded in their memoirs, it felt more like exile than imprisonment.

Given an unusual level of autonomy, the Brothers quickly set to work. They soon established a prison community that some described as a ‘virtuous city’ – a nod to Aristotle’s concept of the polis – and others called ‘Paradise on Earth’. They pitched tents, built mosques, held lectures, staged plays, wrote novels – and even performed stand-up comedy – all while enforcing strict adherence to sharia law and Islamic values in an effort to model the society they envisioned for an Islamic Egypt. Soon, however, the Brotherhood’s ‘utopia’ was showing cracks. Class divisions emerged. According to communist prisoners – detained after a nationwide crackdown following the revolution in 1952 – the Brotherhood’s upper ranks exploited their fellow inmates. Some reportedly kept personal servants; others hosted lavish banquets while lower ranking Brothers struggled to get by. It was a far cry from the egalitarian ideals professed by the Brotherhood.

In 1955 a mysterious man known only as ‘Major Bahgat’ arrived at Camp Wahat. Bahgat was an officer in Nasser’s intelligence services, and he approached the imprisoned Husayn Hammuda – a former army officer and Brotherhood member – with a proposition. As Hammuda recounted in his 1985 prison memoir Secrets of the Free Officers and the Muslim Brotherhood, Bahgat told Hammuda that Nasser wished to reconcile. The president, Bahgat suggested, wanted to expel the British from the Suez Canal and sought the Brotherhood’s moral and political support. The offer was clear: back the regime’s nationalist cause and perhaps your suffering in the desert will come to an end.

Bahgat left behind a transistor radio. Soon, radio broadcasts became a focal point of debate as the Brothers tuned into Radio Cairo, listening to Nasser’s deliberations over the Suez Canal. Each news bulletin, each speech, was dissected for signs of sincerity or manipulation. The intramural magazine al-Sujun (Prisons), which circulated monthly among inmates of Egypt’s prisons, carried numerous articles on Nasser’s standoff with the West.

News of Bahgat’s visit spread quickly among the Brothers, sparking intense debates. Was supporting Nasser in the face of a common enemy a path to redemption or a betrayal? For some of the older, more pragmatic members – especially those, like Hammuda, who had once served in the military – the choice was simple: support Nasser, secure release, and rejoin the fight for Islam another day. But many younger Brothers and hardliners saw any alliance with the regime as capitulation.

The clash between pragmatism and purity grew fierce. Veterans of past struggles remembered their years of imprisonment under Farouk. They knew the cost of defiance, but also the value of survival. Meanwhile a younger generation, raised on the Brotherhood’s own fiery rhetoric and schooled in absolutism, saw any compromise as a violation of their mission to protect the Brotherhood and Islam. Tensions escalated into open hostilities. A young firebrand and later leader of the Brotherhood, Muhammad Mahdi Akif, reportedly stabbed a fellow Brother with a tent peg after a heated argument over Nasser. Some Brothers even branded their more conciliatory peers apostates, evoking the controversial doctrine of takfir (excommunication) that effectively placed fellow believers outside the fold of Islam. By the middle of 1956 the Suez Canal had become more than a symbol of national sovereignty. It had become a litmus test for loyalty within Egypt’s most powerful Islamist group.

Dreams and telegrams

After Nasser formally nationalised the Suez Canal on 26 July 1956 the prison debates intensified. Officers including Hammuda pushed to send a collectively signed congratulatory letter to the president. They argued that opposing Western imperialism aligned with the Brotherhood’s Islamic and nationalist ethos. Operating from Camp Wahat, the ruling organ of the Brotherhood, the General Guidance Bureau (GGB), refused, branding such gestures as ‘humiliation’. With their leader, al-Hudaybi, far away under house-arrest on an island in Cairo, the Brothers of Wahat had no other option but to fight it out among themselves.

One senior Brother, Ahmad Sharit, tried to sway the group by describing a dream he claimed to have had: a crown-wearing calf falling from a throne – an omen, he insisted, of Nasser’s imminent downfall. Others proposed escape plans or even revolts inside the camp. The GGB, fearing chaos, intervened, trying to calm the more rebellious elements of the Brotherhood. Umar al-Tilimsani, a senior member of the GGB, was accordingly dubbed ‘the Balsam’ for the soothing effect his sermons had on the Brothers.

Yet the battle continued. In September 1956, 71 Brothers broke ranks and submitted a letter to Nasser, declaring their support for nationalisation and their will to fight for Egypt. ‘We announce our readiness to defend the neutrality of the homeland until our very last drop of blood’, the letter read. ‘May God grant us success.’ Their plea was patriotic and poetic – an attempt to balance duty to the nation with devotion to God. But for many of their fellow Brothers, it was unforgivable.

Letters and telegrams soon became statements of faith and allegiance. Some who signed did so in secret, afraid of reprisals from their peers. Others framed their support as strategic: cooperation was merely a means of seeking release or future advantage. But intention mattered little. Once word got out, the stigma was instant. Divisions deepened when, on 29 October, Israel – soon followed by Britain and France – launched an invasion of Sinai, seeking to depose Nasser and regain control of the Suez Canal. Known among Egyptians as the Tripartite Aggression, the invasion was short-lived: after pressure from powerful countries in the United Nations, the three countries withdrew their troops by 7 November.

The Suez War was a triumphant moment for Nasser and swiftly became a testing ground for the regime to measure the Brotherhood’s loyalty to the nation, increasingly equated with Nasser himself. Inside Camp Wahat, hardliners coined a term: zahlaqa, Arabic for ‘the slide’. It described the process by which a Brother, lured by hopes of release, would first write a telegram of support, then isolate himself from more rigid members, and eventually renounce the Brotherhood altogether. Intelligence officers greatly encouraged this cascade. We have several accounts of families pressured to convince their sons, brothers, or fathers to write such letters. According to the memoirs of family members, some Brothers did so to ease the suffering of loved ones. Others refused – even at the cost of relationships, marriages, and their standing among friends and colleagues back home.

Stories also abound of family visits turning into emotional standoffs. One young man refused his mother’s tearful plea to write a letter to Nasser, fearing the spiritual cost. ‘Swear to me, Abd al-Rahman’, his mother cried, ‘swear by God that you will write them a letter.’ But Abd al-Rahman chose against doing so. Others lied to relatives, claiming they had already signed and only confessing to the deception years later. For some of the Brotherhood’s hardliners, ‘the slide’ was not just a betrayal of the movement. It was a betrayal of Islam itself. As one imprisoned Brother explained in his memoirs, supporting Nasser would mean endorsing a regime that had tortured faithful Muslims and suppressed the law of God. ‘If I was to write a letter of support it would be as if I had given up on supporting the rule of God.’

By early 1957 the prison authorities could no longer ignore the schism within the Brotherhood. The Suez crisis may have faded from international headlines but inside Camp Wahat its aftershocks continued to fracture relationships. Fistfights erupted. Camp guards reported shouting matches that sometimes turned into all-night standoffs. There was even rumour of a prisoner execution. To contain the tensions, the camp administration separated the two factions. The ‘supporters’ of Nasser were placed in ‘Section 1’, alongside their longtime ideological adversaries the communists. The ‘opponents’, as they came to be known, were isolated in ‘Section 2’, placed under stricter surveillance.

A clay wall was built to divide them, barely a metre high but symbolically enormous. One of the supporters reportedly took a paintbrush and scrawled a phrase across the barrier in thick, defiant letters: ‘A SOCIETY HAS BEEN HACKED TO PIECES.’ From that point on, the two groups functioned as separate entities. They worshipped in different spaces. Meals were taken apart. Quranic recitation circles became factionalised. Allegations that the supporters were acting as informants for Nasser’s intelligence services spread. Some supporters were said to have received special treatment – better food, relaxed conditions, even earlier release dates. While these accusations were not always substantiated, suspicion, once seeded, took root. ‘This government is unbelieving, and we do not speak to unbelievers’, one opponent reportedly explained to an imprisoned communist.

A new Brotherhood

Within ‘Section 1’, the supporters began to imagine a different future for the Brotherhood. If reconciliation with the regime was possible, perhaps they could still play a role in Egypt’s political life – if not as rulers, then at least as influencers. Some even proposed forming a breakaway movement, a new Islamic association, free of the absolutism that had paralysed the old Brotherhood. They envisioned a pragmatic, politically flexible organisation that could serve Egypt while maintaining its religious identity.

A draft report of this ‘Breakaway Society’, smuggled out by imprisoned communists and sent to their exiled leaders in Paris, laid out its rationale. It was not about betrayal, the supporters insisted, but about adaptation. Egypt was changing and the Brotherhood must change with it – or risk irrelevance. The report spoke of ‘volunteering in defence of our country’s sacred battle against injustice’, emphasising national duty as a religious imperative. They cited precedents when the Brotherhood had cooperated with secular politicians in the name of national interest. Even Hasan al-Banna, the Brotherhood’s revered founder, had once worked alongside Egypt’s corrupt political elite to advocate for independence at the United Nations.

But this argument fell on deaf ears among the opponents. Such pragmatism was nothing but apostasy in disguise. The supporters had been duped by the state’s honeyed words and false promises. Worse still, they viewed this willingness to compromise as evidence of weakened faith. What else would the supporters be willing to bend on?

The psychological toll of this schism cannot be overstated. Many of the supporters who were eventually released or transferred to more lenient prison facilities carried a burden of shame. Though they had walked free, they found themselves ostracised by the wider Brotherhood. Some were branded traitors. Others were quietly sidelined from positions of leadership. One young prisoner, hospitalised after vomiting blood, reportedly pleaded with a fellow Brother to help him rejoin the Brotherhood. ‘Help me, Ali! Say to your Brothers that they must forgive me’, he begged. The answer, as recorded in a prison memoir, was cold: ‘Repent – and stop writing reports about other Brothers!’

The test of God

One question haunted many Brothers, long after the dust had settled: had they been tested by God or trapped by the state?

A few became convinced that God had turned His back on the Brotherhood, and ultimately began questioning their faith. But for most, the answer was both. The regime had certainly exploited divisions, sowing suspicion, offering conditional freedoms, and measuring loyalty by telegram. Some believed that divine will was at play – that the ordeal was meant to separate the sincere from the opportunistic. That those who stayed true in prison would be rewarded in the hereafter, even if they never saw freedom in life. This theological framing became essential to the Brotherhood’s long-term survival. It allowed members to narrate their pain not as defeat but sanctification, reframing failure as martyrdom. By the end of 1957 what had started as a political debate over Nasser’s policies had transformed into a full-blown moral crisis, and while the Brothers were eventually moved to other prison facilities in Egypt, the wounds inflicted in Camp Wahat would not easily heal.

During the prison years of the 1950s and 1960s, the Brotherhood’s experience of the Suez crisis came to be known as the ‘Trial of Support’. For those who lived through it, it was more than metaphor. ‘Supporter’ and ‘opponent’ became identities, shaping reputations for decades. For some, the stain of support for Nasser proved impossible to wash off, regardless of their intentions. Others, perhaps unfairly, were elevated as paragons of steadfastness. These judgements were often more social than theological, driven by the Brotherhood’s need to preserve a sense of moral clarity after years of imprisonment and betrayal.

The story of the supporters and opponents took on legendary status among Brotherhood chapters in exile. In Syria, Jordan, and the Gulf, leaders cited the events of 1956-57 as cautionary tales, warning members about the dangers of factionalism and the price of wavering commitment. For a movement that prized unity and moral discipline, the notion that Brothers had once turned on each other – sometimes violently – was sobering and instructive.

Crackdown

The Suez crisis was a moment of great national significance for Egypt. Nasser’s bold defiance of the Western powers made him a hero to many across the Arab world. But for the imprisoned Brotherhood, the question was never just about the Suez Canal. It was about what it meant to be a Muslim in a state that denied Islamic law. What it meant to serve a nation that had jailed you. What it meant to remain faithful to God when your family was starving, when your comrades were signing letters of support, when your leaders could no longer command unity.

Yet this moment of crisis also marked the Brotherhood’s maturation. Forced to confront its own contradictions – between ideals and realpolitik, community and creed – it became more politically self-aware. The divisions forged in Camp Wahat would go on to shape the movement’s internal politics well into the 1970s and 1980s. Veterans of the Suez split carried their grievances with them into positions of leadership – or were excluded by those who had never forgiven. In some cases, those tensions directly influenced the Brotherhood’s responses to later challenges. In the early 1970s President Anwar Sadat sought to co-opt the Brotherhood to counterbalance the influence of leftist and Nasserist forces, releasing many of its members from prison, permitting some limited public activity, and turning a blind eye to its social and educational outreach. In return, the Brotherhood largely refrained from open political opposition and maintained a relatively moderate stance. However, this uneasy alliance gradually eroded as Sadat’s regime embraced economic liberalisation, normalisation with Israel, and autocratic rule. Meanwhile, the vacuum created by the Brotherhood’s cautious approach allowed the rise of more radical Islamist groups – such as al-Gama’a al-Islamiyya and Egyptian Islamic Jihad – in the late 1970s and 1980s. These groups, often composed of young militants disillusioned with the Brotherhood’s moderation, favoured confrontation with the state, culminating in high-profile acts of violence, including the assassination of Sadat in 1981.

Today, following a renewed crackdown on the Brotherhood in the wake of the Arab Spring of 2011, more than 40,000 Brothers face a new ordeal in Egyptian prisons. In 2012 the Brotherhood-backed candidate Mohamed Morsi became Egypt’s first democratically elected president. His brief presidency was abruptly ended by a military coup led by Egypt’s now-president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in 2013. The Brotherhood was subsequently designated a terrorist organisation, with Morsi himself among the thousands arrested, dying in prison under mysterious circumstances in 2019.

A similar scenario has recently unfolded in Jordan, where the Brotherhood had long operated legally, with members sitting in parliament. The Jordanian government banned the group in early 2025, citing some members’ alleged involvement in a violent plot within the country and claims of arms support for Palestinian militants in the occupied West Bank. Elsewhere, the Brotherhood’s status remains contested. While the European Union has not classified it as a terrorist organisation, debates within member states – particularly Austria, France, and Germany – reflect rising concerns about its influence. In such contexts, the Brotherhood often becomes a focal point – and, at times, a bogeyman – for broader questions about the political engagement of Muslim communities in Europe.

Mathias Ghyoot is a PhD candidate at Princeton University and the author of Brothers Behind Bars: A History of the Muslim Brotherhood from the Palestine War to Egypt’s Prison (Oxford University Press, 2025).